Patrick: I would like to welcome readers to this special edition of At the Scene of the Crime! This blog was started when I wanted to vent my fury over the abysmal book by George Baxt, The Affair at Royalties. I had written an online rant about the book’s failings and was so furious about them, I sat down and created a video thoroughly bashing it. (I still attend group therapy and hope to get over it someday.) Needless to say, I come across as rather “shouty” and I consider the video far from my finest review. However, I got relatively positive feedback, and soon enough, I had created this blog and was posting in it regularly. Things were going well and I had just about forgotten about George Baxt...

Until, for his “Q” entry for the Alphabet of Crime Fiction, Sergio (from Tipping My Fedora) wrote about Baxt’s A Queer Kind of Death. Not only did he praise the novel, he gave it five fedora tips! I was stunned to even see a positive take on Baxt, and it was so well-written I wrote the following in my comment: “The book I read was atrocious in every way- you have now successfully made me doubt my conclusion that Baxt had no talent.” The disagreement was an interesting one which immediately guaranteed my readership of Sergio’s blog.

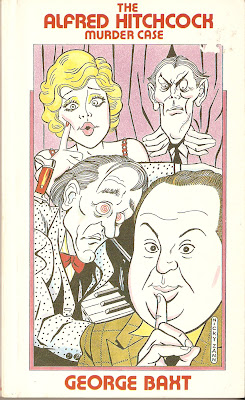

And then I had an idea: as we saw Baxt’s work from two different vantage points, why not read a book of his together and collaborate on a crossover review? I asked Sergio to contact me, pitched the idea (which he liked), and we selected a book: The Alfred Hitchcock Murder Case.

Now what motivation could I possibly have had for returning to the work of an author whose book I thoroughly despised? Quite simply: curiosity. I was curious what people like Sergio or William DeAndrea saw in Baxt to give him such positive appraisals. After all, it’s quite possible The Affair at Royalties was his The Hungry Goblin or Elephants Can Remember. So I decided to give Baxt another shot, trying to cast aside the prejudices of my experience reading The Affair at Royalties. And who knew? Perhaps I’d enjoy it…

Thanks for joining me today, Sergio!

***

Sergio: Buon giorno Patrick,

it's great to be here and thanks very much for having me on your splendid blog - despite my fondness for Baxt! This was a great suggestion of yours and between us we should be able to debate the pros and cons of the author's approach to life, the movies, literary crime and crimes against literature (not necessarily in that order). We've deliberately chosen to stay away from A QUEER KIND OF DEATH and its sequels as it seemed more profitable (and more fun) to pick one that neither of us had read before. THE ALFRED HITCHCOCK MURDER CASE certainly fits the bill - it's the second of Baxt's 'celebrity sleuth' series which combine actors, writers and filmmakers with fictional crimes. The approach is not too dissimilar from Stuart Kaminsky's Toby Peters series except that the real person becomes the actual detective. And Alfred Hitchcock, the self-styled 'master of suspense' seems a likely candidate for this kind of fictional treatment given his love of thrillers about an innocent man on the run (and personal publicity).

The book begins in Germany in 1925 where 'Hitch' and his fiancée Alma are working on THE PLEASURE GARDEN, his directorial debut. The tight production schedule gets interrupted however when the script girl is found dead in the shower, knifed to death ... hmmm, sounds familiar ...

***

The Alfred Hitchcock Murder Case is divided into three parts. The first part, taking place in 1925 Germany, is the best one for my money. The beginning is honestly just plain weird: it starts with some sort of nightmare Hitchcock is having, and it more or less serves to be bludgeon you over the head that Alfred Hitchcock is the main character, as he cries out just how afraid he is of the police, that his father doesn’t love him, and he’ll have no improvisations in this scene.

There’s this weird dichotomy to Baxt; at times, he can be delightfully witty, but at other times, his jokes are so forced, it’s like trying to crack open a walnut with a sledgehammer. The best illustration, I think, is a scene where Hitch and his fiancée, Alma Reville, are in a taxicab. Hitch is frustrated with the movie he is filming, The Pleasure Garden, and he cries out that what they really need is a rape scene. As he and Alma discuss what the rape would entail, I wasn’t particularly amused… but at the same time, the taxicab driver’s alarmed reactions had me chuckling out loud. It was a bizarre combination of something extremely funny and the “you’re trying way too hard” brand of comedy.

However, after a while, things settle down nicely. As you say, death interrupts shooting when a script girl is murdered in her shower, stabbed twenty-nine times. There are plenty of references like this to Hitchcock movies, and they work best in this first part. He has shot none of these movies yet, and so it’s a fun tip of the hat to the reader. I’m a big Hitchcock fan, so it was rather fun to see him label something as a delightful idea and then file it away to be used in a movie years later.

The shower murder is also where the book really picks up steam. The ensuing investigation is interesting, and a second murder occurs under everyone’s nose, a murder that is both intriguing and complicates the plot. The plot twists again when the victim’s daughter goes comatose (What is Baxt’s obsession with the comatose state?) and she disappears from her sanatorium overnight (probably not of her own free will)…

Also, the first part of the book contains my very favourite bit, as Hitch tries to convince Michael Balcon to lend him money, while Balcon tries to find out about the police investigation:

“It is unpleasant being short of funds!”

“What about the police?

“I wouldn’t dream of borrowing from them!”

***

You’re probably right to single out the first section as being particularly noteworthy, not least because it deftly provides lots of genuine clues and plot elements that will be followed up later in the story but also because it provides a surprisingly tender depiction of the relationship between Hitch and Alma. Indeed, although the book goes out of its way in its disclaimer to ensure readers that this is a work of unauthorised fiction, Baxt shows great sympathy in depicting the warmth and closeness of their relationship, which of course was both personal and professional and would remain so for the rest of their lives. There are lots of nice bits of repartee along with some real gallows humour, which is contrasted in one of the best set pieces in the book when Hitch and Alma have dinner with Fritz Lang and his screenwriter wife Thea Von Harbou. I really liked the way we see Hitch and Alma at the beginning of the professional careers and their romantic partnership while Lang, who has just made Metropolis and is the toast of the town, is much more worldly-wise and puts up with the nagging Von Harbou, who makes odious anti-Semitic remarks which they all ignore as no one can stand her anyway. In fact she would remain in Germany as a dedicated Nazi even after Lang had fled the country, so this is all pretty historically accurate.

Baxt’s humour is occasionally a bit clumsy and probably a bit questionable, as you say, though this is used most often to explore Hitch’s defence mechanism against his many insecurities - though at one point even the loving Alma says to him, “Skip the levity and concentrate on the facts”. Equally though Baxt martials a large cast of characters with great ease and I was really sorry when Inspector Farber failed to make a reappearance in the later sections – but along with its rich gallery of characters there are lots of really droll lines and descriptions, like the last line of chapter 3: “Rudolf Wagner had fallen across the keyboard, a knife in his back and a frown on his face.”

I really enjoyed all the movie references too - but then, as a card-carrying film buff and aficionado it would have been funny if I hadn’t. In fact I made a point of reading most of this book while listening to some classic Hitchcock movie film scores by the likes of Bernard Herrmann and Franz Waxman to get me in the proper mood. It is certainly a bonus in this kind of meta-textual rewriting of film history to have one's film buff credentials flattered by all the slightly more obscure movie references though some are more obvious than others especially when it comes to character names - some might not find it as amusing but I quite liked that the head of the British secret Service is called Sir Arthur and his two trusted lieutenants are Basil and Nigel, presumably after Doyle, Rathbone and Bruce respectively. However I also found that when the book skipped a decade to 1936 in the second part, I ended up wishing that Baxt's movie references were a bit more obscure as some are not only just too damn obvious but even spoils the fun by pointing some of them out!

While part one is a pretty traditional whodunit with a close-knot cast of characters, the second portion is modeled very closely on the ‘innocent man’ thrillers Hitchcock had become famous for at the time, such as ‘The Man Who Knew Too Much’ and ‘The Thirty-Nine Steps’, employing the fairly post-modern device of having Hitch receive a manuscript which will end up guiding him throughout the rest of the book. Hitchcock and Alma in fact end up following becoming the characters in a scenario for which the ending has yet to be written but for which many of the elements are extremely familiar – I think Baxt just about gets away this conceit, but it is a bit of a struggle though and the sense of strain does show in several places.

***

I’m glad you brought up the relationship between Hitch and Alma. The relationship is really well-handled and sensitive, and overall, it was rather charming- one of the book's best features.

That being said, there is a definite transition from the 1925 portion to the 1936 portion of the book. For one thing, you never do find out whodunit in 1925 (that is only revealed in the finale). But also, I thought that it was in the 1936 storyline that Baxt lost his grip and the book started sliding downhill.

For one thing, the references to Hitchcock become too obvious, to the point where even the characters comment on the similarities. What annoyed me was that Baxt stole about 2/3 of his plot from Hitchcock but tries passing it off as delightful references to his work. In most cases, it just doesn’t add up. It makes sense for Hitchcock to run across a melody that is really a coded message— after all, he is just about to film The Lady Vanishes. That is a legitimate and good tip of the hat to the man. But large chunks of plot are stolen directly from The Thirty-Nine Steps or Young and Innocent, which Hitchcock has already filmed. It is no longer a clever reference, it is just silliness that Baxt copied and pasted into his story. (At least, he would've if Nicky Zann's delightful caricature of him was sitting at a computer.)

At first, the thriller portion is actually fairly good: a man Hitch and Alma knew in Germany telephones and tells Hitch he has a script Hitch will be interested in, and he sends his friend over to deliver it. The friend manages to do that, but winds up stabbed in the process and the script just barely manages to get into Hitch’s hands. After a few mix-ups, Hitch finds himself on the run (having apparently committed a murder), Alma is kidnapped, and the game’s afoot.

The turning point is when Hitch goes to a church and confronts the vicar, Lemuel Peach, who acts in most un-vicar-like ways. Hitch soon deduces that the man is not who he claims to be, avoids getting stabbed, and runs away from the scene… But when the police show up, the false Lemuel Peach has been stabbed himself.

This is where I started asking myself: why was the fellow there? You eventually find out who he was (and the answer is silly beyond belief), but just what was he doing there at that time? No reasons are ever offered. Logic is thrown to the wind. You could argue that it is an homage to Hitch’s “icebox” scenes, but the reason those scenes worked was because Alfred Hitchcock was a brilliant director, who could turn the worst plots into thrilling movies. George Baxt is not nearly as good as a writer, and the questions keep popping up. By the end, the script (more or less plagiarising half the movies Hitch had already made, with a good smattering of his upcoming one, The Lady Vanishes, thrown in for good measure) becomes maddening. Everything therein happens just that way in real life for no reason. There is no way to control such events! Who was orchestrating the people to be in precisely these places at just the right times? It’s never answered and adds to the dissatisfaction.

Not only that, the spy-thriller elements just become silly, and I doubt even Hitchcock could disguise that. After all, this is a plot that involves a Nazi midget spy dressing up as Cupid and murdering people with arrows. (I wish I was making that up.)

***

The latter parts of the book are definitely a bit less fun and feel more laboured in parts, but I also thought there were lots of good things. I thought the transition to 1936 was handled fairly well and you can’t really complain that you don’t find out ‘whodunit’ in 1925 until the end, surely … In terms of the pastiche plot, I think you are being a bit too harsh in demanding ironclad logic for the scenario – surely the whole point is that the scenario delivered to Hitch is meant to resemble his movies but at the same time I thought that Baxt was fairly smart in suggesting that of course there were real-life sources (like Buchan) for the fictional stories inspiring the screenplays he was shooting. It is in the nature of a pastiche that the plotting not be completely iron clad but more about enjoying the patchwork of references and allusions.

You mention the cherub bit being very silly, which it is, though it is also a homage to Tod Browning's 1932 horror classic Freaks and of course Hitchcock’s own ‘Saboteur’, the suggestion of course being that this would influence his later filmmaking choices, like the glass of milk in the climax recalling a famous sequence in Suspicion. Do they progress the plot much? No, not really, but I thought they were meant to be outrageous. On the other hand, there were maybe a few too many references to Young and Innocent, although I really liked one bit of description when the musician with the facial tic is killed: “His tic was going wild like a semaphore in distress.”

In plot terms I think we are meant to assume that the heroes and villains are in a way orchestrating Hitch’s actions and shaping events, willing them to follow the scenario, because of course both sides want to unearth who the double agent is and so are both equally responsible for manipulating Hitch and for creating a reality borne of fiction where he can hopefully give them the information they need – I actually thought this was a fairly sophisticated bit of ‘tongue-in-cheek’ postmodernist plotting, though I suspect you will be having none of this!

***

I see poor phrasing is once again my undoing! Just to clarify: I’m not complaining that you don’t find out who the 1925 killer is until the end; I was simply pointing out how the book transitions, leaving the question open and then going through to the 1936 storyline, where it will eventually be answered.

Some social commentary was forced into the book. The detective from 1925 Germany, Wilhelm Farber, is mentioned once or twice in 1936, where we found out the Nazis murdered him outside of Dachau, where he’d gone to investigate “something” (the inference is clear). This prompts the line “Why would anyone want to be found dead in Dachau?” from Hitchcock. I stared in disbelief. I didn’t know if Baxt was trying to do social commentary, be funny, or both. Whatever it was, it failed dismally. (Perhaps I’m being unreasonably sensitive about such a thing, but I knew someone who was in the concentration camp at Dachau, and heard a first-hand account of life there.)

Baxt’s mystery is very weak overall, and it did not manage to fool me. The stuff is easily guessable, and it’s almost laughable when Hitch acts surprised to find out that Obvious Villain No. 23 is, in fact, a villain. However, I have to praise Baxt for one clue that was expertly hidden, although to be honest, it was hidden in what sounded like a domineering person’s psychotic ramblings. Still, it was the only element of the plot that surprised me, and the clue was there all along, escaping evasion until you found out its significance.

***

The Dachau reference of course is truly chilling (Baxt himself was Jewish) and I suspect that the author was trying to point to the fact that many people didn’t yet know how bad things were going to get – but I agree, as irony goes, it’s very heavy handed – it’s certainly not meant to be taken lightly but it’s probably plausible as the kind of remark that might have been made at the time.

The unmasking of the traitor at the end is not as a big surprise as it should have been probably although I thought it was quite well done all the same – but the story could definitely have done with a few more twists and turns as it does get a bit predictable, though I thought the final revelation of the MacGuffin was amusing (if also perhaps a bit transparent).

Mainly though I really wished that Alma could have been more of an active participant – I think that it is her absence in the latter parts of the plot that hurt the book a bit. In later volumes of his ‘celebrity sleuth’ series Baxt would focus on famous couples and I think that may have been a belated acknowledgement of this weakness here.

***

You bring up a good point: by the end, Alma sits around and waits to be rescued, reminding us of her existence every 40 pages or so. It would’ve been a lot nicer to have her running around with Hitchcock, and it would’ve added a bit of unpredictability to the plot, which adheres too rigidly to a fictional screenplay, with elements it is next-to-impossible to control.

Overall, out of 4 stars, I’d give The Alfred Hitchcock Murder Case 1.5. Its first part and a good chunk of the second are genuinely fun to read through, and when Baxt gets something right (like a reference to a Hitchcock film), he really gets it right. Unfortunately, when he does something wrong, he really gets it wrong— and by the end, he was doing too many things wrong. While a decent homage to Hitchcock, it’s too predictable and silly, and its finale is something of a mess. Also, I’m no fan of postmodernism, so the whole idea with the script started to rub me the wrong way by the end.

Patrick's Rating: 1.5/4 stars

***

On the whole I find myself concurring with you here - much as it pains me to admit it, this book is without question a bit of a mixed bag with good jokes, nice dialogue, some good set-pieces but also an increasingly meandering story by the end, and probably a few too many elementary movie references. I would probably give it a slightly higher mark - 2 tips out of five for the general excellence of the first half and an extra one for the the frequently witty dialogue - in total three fedora tips out of five, which is basically the same mark as yours with just a smidgen bit more.

It is certainly not in the same league as A QUEER KIND OF DEATH (which I really hope you will get round to reading some time).

Thanks very much for letting me play in your sandbox Patrick, it's been a treat.

***

And thank you again for joining me! It’s been an interesting conversation, and I’ve enjoyed it very much!

First of all, before commenting on this review, I have to note that the yellow text on a purple background is giving me all kinds of new mental afflictions!

ReplyDeleteAnyway, this is a very interesting and in-depth review, but still one that failed to entice me to jot down his name on my wish list. Baxt seems to have been an author who was too busy with being funny that he didn't notice that the plot had slipped from his grasp. I guess he was better suited for the satirical novel rather than comical mysteries.

Well, a purple background does somewhat limit the options as to text colour, but I went for legibility here... Besides, purple and yellow were the team colours in my first high school, so I think they go together nicely. ;)

ReplyDeleteI have to admit this book dispelled my view that Baxt had no talent whatsoever, but at the same time, it doesn't make a great case for him as a consistently good writer. I will probably read more Baxt in the future, but I'm not going to trample everyone in line ahead of me to get to his books.

I think you just don't get camp, Patrick. I'd read this book and laugh uproariously. A Nazi midget murderer! Sign me up for my copy now. BTW - I read THE AFFAIR AT ROYALITIES at an age younger than you are now. I thought it was pretty darn good. But then I was also drawn to lurid books at an early age. Who knows what I'd think of it 30 years later?

ReplyDeleteThere's a book called "1001 Nights" or something of the sort, in which Bill Pronzini, Marcia Muller, and others recommend mystery novels. The only one by George Baxt is "The Affair at Royalties", but all the reasons given there for reading it were the very reasons I hated the book!

ReplyDeleteJohn, by the time the midget murderer shows up, it becomes obvious that the plot is going nowhere, I'm afraid... by then, for me it was a question of "how many pages are left?"