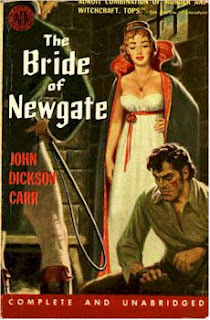

The opening of The Bride of Newgate is stunning. Dick Darwent is in a dark cell in Newgate Prison, awaiting to be hanged in the morning. Meanwhile, Lady Caroline Ross confers with her lawyer, Elias Crockit, and Sir John Buckstone. According to her grandfather’s will, Caroline is to marry before her 25th birthday, or else she will lose her rights to her grandfather’s fortune. The lady finds the prospect of marriage distasteful, and is bitter at her grandfather for creating such a will:

“Do you recall,” Caroline said dreamily, “any particular phrase in the writing of that will?”

“I have forgotten it.”

“I have not. ‘She’s a stubborn filly, and needs the whip.’ — Let us see!”

Caroline eyes Dick Darwent as the perfect escape— she will marry him, pocket her grandfather’s money, and then watch with joy from her champagne breakfast as Dick Darwent is hanged from the neck until he is dead. Dick has nothing to lose, and is offered 50 pounds, which he intends to leave to his lady-friend, Dolly…

Thus begins The Bride of Newgate, one of Carr’s greatest books ever, period. Its opening is marvellous and sucks you right into the action. The plot begins with a bang and is both fast-paced and fascinating, as it twists and turns and arranges itself into shapes that would stun even a professor of geometry. Carr even manages to sneak in an impossible situation, as Dick Darwent’s defense depends on a room that seems to have vanished into thin air…

The solution to the impossible trick is satisfying: its general idea is apparent enough, but its details are elusive, and they are very rewarding once revealed. Not only that, the culprit’s identity is a genuine shocker. (Unlike whoever approved the Four Square cover of Swan Song, I refuse to say more.)

There is plenty of historical colour in The Bride of Newgate— far more than in The Ghosts’ High Noon. You can feel Carr’s enthusiasm for history leap off the page, as palpably as if he were discussing it with you over a glass of sherry. (Petri California Sherry! … Okay, I’m sorry, I couldn’t resist.) There is also a marvellous atmosphere of adventure throughout the entire novel, but also of danger: the book gets very, very dark at times.

Meanwhile, surprisingly for Carr, his characterizations are brilliant. One of the most interesting characters in all of Carr is the Reverend Horace Cotton, Ordinary of Newgate. He is apparently an actual historical figure, and in my opinion, Carr’s best ever priest character. Priest and psychologists, for Carr, are usually figures of fun— thus we get a crime-solving bishop sliding down bannisters in The Eight of Swords. Cotton is nothing like this— in the opening, when the villainous Sir John Buckstone beats down a chained, helpless Dick Darwent, Cotton stands in his way, standing up against the injustice that allows a nobleman to whip a chained prisoner:

“Sir,” the clergyman said quietly, “Observe that I am even less a weakling than yourself.” Then his tone changed. “Raise your hand once more; and by God’s grace I will flog you through Newgate with your own whip.”

Carr romanticized history, but he was not blind to the cruelty that could occur in the past. Then Carr, an agnostic for most of his life, has the Reverend discuss the idea of faith with Dick Darwent, who has expressed opinions uncannily like Carr’s. Dick, seeing the priest stand up for him, declares that he believes in God, because if a man like Cotton believes in Him, he is a fool not to believe as well. The priest doesn’t eagerly ask him to donate his 50 pounds to the Church; in fact, he candidly tells Dick he doesn’t truly believe, despite his protestation… his words are a misplaced sense of gratitude. To see Carr create such a marvellous character is flabbergasting, and it tears apart the argument that Carr couldn’t “write characters”. He could do just that: he just preferred to write plots without characterization intervening.

I have only one complaint about the entire novel, and that is the behaviour of Mr. Mulberry, who makes an uncanny habit of keeping his deductions from page 37 all to himself until an appropriate moment on page 102. In all fairness, though, this complaint is unimportant and ignorable nitpicking; without it, such a breathlessly dazzling plot would not have been possible. Once all is explained, however, Mulberry’s actions become quite understandable. It reminds me of this fragment of Helen McCloy’s Dance of Death:

Up to this moment, he had been sustained by intellectual curiosity. The mystery had seemed more important than the murder. It had challenged him like a problem in chess or mathematics.

But now that it was no longer a mystery, he realized to the full that neither was it a game played with senseless pieces, nor a problem living only in the mind of a mathematician. He was dealing with human beings like himself who could feel and hope, think and suffer…

Indeed... Mr. Mulberry’s defense has already been written quite admirably for him. (The quote from McCloy I just used is so perfect, I propose to immortalize it on my blog, as I did with H. R. F. Keating’s.)

This, undoubtedly, is the finest Carr I’ve read since Fear is the Same, and both books are among the best I’ve had the pleasure of reading in 2011.

***

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, have you reached a verdict?

We have, m’lord.

How do you find the defendant?

We find the defendant, John Dickson Carr, guilty of writing a flat-out masterpiece with intent to entertain.

Well, I should've seen this one coming. Here I'm, being as good as gold and not bothering anyone, jubilantly about the fact that I ordered a copy of this book – only to discover that I was beaten to it... again!

ReplyDeleteYou and John really ought to be ashamed of yourselves!

Probably the best historical Carr, in my opinion. Excellent review.

ReplyDelete@ TomCat

ReplyDeleteWell, considering that you've beaten me to reviewing a book several times now, I think it's poetic justice... And as I said back in my first post, I abstained from Carr for far too long.

@ Bob

Thanks for the kind comment, and I am inclined to agree. It's one of Carr's very best- whether better than FEAR IS THE SAME or THE DEVIL IN VELVET, I don't know...

Again, bravo for this very interesting blog.

ReplyDeleteI think it is one the best among the late books by Carr, and perhaps the most entertaining novel among his historical books. The enigma of the disappearing room results from a bet between Carr and Clayton Rawson, and I found his solution very convincing. The mystery, albeit being a constraint, is well integrated in the plot of the novel.Certainly a must read.

Merci, Gregory, for commenting- and thanks for the kind words!

ReplyDeleteI agree: this is one of Carr's best post-WWII books. Carr and Rawson liked to bet each other in this kind of way- that's how we got the excellent "He Wouldn't Kill Patience" (and Rawson's "From Another World") and the rather poor "Scotland Yard's Christmas" (I can't recall the name of the Rawson story with the same premise, though).